Students and staff beliefs on social media censorship create a guideline that may prove useful

In a problem that’s stemming from both the proliferation of social media use and campus violence, universities are considering what’s appropriate to censor on social media and what’s not, often leading to confusion and infringement of students rights. But a new guide may be able to help.

In a problem that’s stemming from both the proliferation of social media use and campus violence, universities are considering what’s appropriate to censor on social media and what’s not, often leading to confusion and infringement of students rights. But a new guide may be able to help.

Free speech, which has always been a hot-button topic for higher education and continues to be, has never been more confusing than with the explosion of social media forums over the last five years. A confusing issue that John Rowe, academic registrar for Curtin University in Australia, thought worth an intensive study.

“All universities have been struggling to balance freedom of speech and the right to express an opinion, with reasonable expectations of responsible and respectful behavior by students, as well as the protection of staff and student well-being,” says Rowe in his study, “Student use of social media: When should the university intervene?” published by the Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management.

In the study, Rowe surveyed students and staff at Curtin during 2011—with rigorous surveys (which you can read about more in the report)—which lead to the development of a categorization model and guidelines for handling matters of censorship on social media.

The guide aims to help colleges and universities navigate the murky waters of social media, free speech, slander, and potentially illegal remarks.

(Next page: What students and staff are saying)

One of the main issues with students posting ‘negative’ or ‘inappropriate’ comments on social media sites, explains Rowe, is that the university is at a loss of what its responsibility is to the well-being of staff and students and whether or not it warrants a response at all.

Of course, the other main issue is that if the university believes the social media comment to be ‘offensive’ or ‘inappropriate,’ and they ask the students to take the comment down from their personal account, is that an infringement on students’ freedom of speech?

The report aimed to understand these concerns more fully, as well as find solutions to them, specifically by surveying the students and staff at Curtin (you can read more about what the report sought to answer here). Here’s what the survey found:

1. There was wide consensus among both staff and students that the most serious categories of comments are threats of violence, racist, sexist and homophobic comments, and admissions of implication in academic misconduct (cheating and plagiarism).

Rowe believes that this finding “reflects a high degree of awareness of what constitutes illegal behavior and also the high value placed on academic integrity in a university community.”

2. In general, the types of comments noted above were considered more serious if made about staff than students, with the “most serious” post to be the “threat to a staff member,” followed by “racist comments about other students and staff.”

3. 72 percent of students “emphatically” said that non-university, student-run sites and accounts should not be monitored by the university. Though staff tended to agree, only 54 percent gave an emphatic ‘no.’

“Social media is a way for students to connect outside of the university,” said one student respondent. “Just as I would happily discuss a tutor I wasn’t pleased with friends at a coffee shop, modern communication makes it so that I can communicate these issues with friends on the internet. My personal communication outside the university is my own and I would feel incredibly intruded upon if the university contacted me about something I said online when venting frustrations about a unit or a tutor or university program. It would be in the best interest of universities to stay out of the affairs of students in social media settings unless there were some absolutely defamatory comments made (this means going over and above ‘venting’ and saying things that are untrue or slanderous about a staff member or bullying another student online).”

4. A large concern among students and staff is that if universities do start to monitor non-university sites, would universities create the impression that all university-related but student-run sited be monitored?

“This raises possible liability issues for the university if illegal or particularly damaging comments on such sites are not dealt with,” explains Rowe. “There is also the potential that actively monitoring and reacting to comments on unofficial sites could undermine the value and effectiveness of formal feedback mechanisms.”

Both students and staff suggest that if comments fall under the ‘serious’ category, the university should leave the matter up to the police or social media platform provider.

5. A high proportion of staff believe that their employer (the university) has an obligation to take action regarding negative posts, particularly those that are “derogatory or personally insulting,” in order to protect their “health, well-being and reputation.

For example, said one staff participant, “Students need to realize that comments that they make on social media influence the opinion of others and may have far reaching implications for both themselves and the object of their criticism. For example, written negative comments amount to slander and can carry legal consequences if pursued. In addition, employers now use Facebook and other social media as part of their vetting process when selecting new employees and so a negative Facebook profile also hinders the student’s own chances of success in the future.”

However, some staff also believe that the university should not try to stifle these outlets. “What people do in their personal, private lives has no relevance to the university. If it’s on a university provided forum, sure, take action, but interfering in their private lives is wrong. Functionally it’s the same as monitoring what they say in their lounge room, because we don’t provide that resource either.”

6. The majority of student respondents said that they would not welcome contact from universities, even constructive contact, regarding comments they had posted on student-run sites.

(Next page: The guideline)

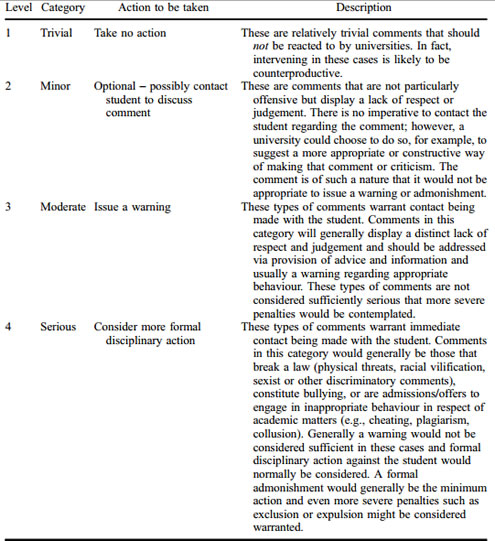

Based on these survey responses, Rowe and Curtin developed a guideline to help not only their universities, but others, navigate social media censorship by rating comments on a scale:

For more in-depth information on the survey’s findings, it’s conclusion, and the problems identifying social media users, read the full report.

- 25 education trends for 2018 - January 1, 2018

- IT #1: 6 essential technologies on the higher ed horizon - December 27, 2017

- #3: 3 big ways today’s college students are different from just a decade ago - December 27, 2017