Paul J. LeBlanc, the president of Southern New Hampshire University, thinks the “American dream” is dying. Or, at any rate, it’s a dream that’s moving to other countries, but could return to the U.S. via online degree.

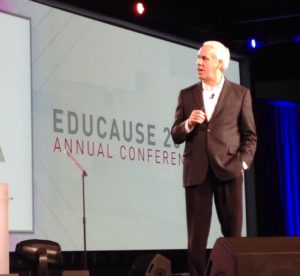

LeBlanc, who was a first-generation college student, closed out the 2013 EDUCAUSE conference Oct. 18 in Anaheim, Cal., by asking for a show of hands.

“How many of you are also first-generation college-goers,” he asked a sea of college representatives.

Hands shot up all throughout the auditorium.

“So we lived, as it turns out, the American dream, but that story today is actually more the Danish dream,” he said. “Because that kind of social mobility happens more often now and more easily in places like Denmark rather than the United States.”

But LeBlanc said there’s a way to fix what he thinks is a now-broken system, and that’s by using online education to reach the thousands of students who are still considered “non-traditional,” despite their demographic now making up the majority of degree-seekers.

Under LeBlanc’s guidance, Southern New Hampshire University has been — for better or worse — a pioneer in online learning, becoming the fourth largest American non-profit provider of online degrees.

The university began addressing this group of students, LeBlanc said, by first asking “which higher education are we trying to fix?”

American higher education doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone. To some, it means a college sports team and the controversy surrounding paying student athletes. To others, it means private, elite schools that are as much about status as education. To faculty, it could mean research and the nature of tenure.

See Page 2 for details on why LeBlanc thinks the credit hour is a flawed system.

And then there’s the most common idea of an American college: the dorms, the tree-filled campus, the classic coming-of-age experience.

The majority of students that online education serves — adult learners with families and jobs — don’t need any of that, LeBlanc said, nor do they particularly want it.

“They’ve got more coming of age than they can deal with,” he said. “Thank you very much.”

And that’s an important thing to remember when a university puts together an online degree program, LeBlanc said. There are very different kinds of students out there, and education is not a one-size-fits-all service.

Take the concept of a credit hour, LeBlanc said, something that is now engrained in the very DNA of a college degree but was created by Andrew Carnegie simply for faculty pensioning purposes at the turn of the 20th century.

Would, then, the credit hour make sense for an online degree program that doesn’t actually include faculty teaching, such as Southern New Hampshire University’s College for America?

“The credit hour is good at telling you how long someone sat,” LeBlanc said. “It’s not good at telling you what someone learned.”

The changes that online education may bring to higher education shouldn’t be seen as a threat, LeBlanc said. Its purpose is not to replace the traditional on-campus experience, but to provide an alternative for students left out of the that model.

“These students are not coming to my campus, anyway,” LeBlanc said.

Follow Jake New on Twitter at @eCN_Jake.

- What does higher-ed look like in 2023? - January 5, 2015

- Are ed-tech startups a bubble that’s ready to burst? - January 1, 2015

- Are MOOCs really dead? - August 28, 2014