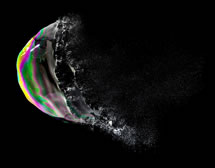

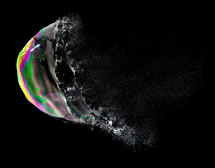

Ed-tech startups raised more than $500 million in funding in the first quarter of 2014 alone, but some investors are worried about a bubble

When Matthew Pittinksy and the other founders of Blackboard attempted to find funding for the then-fledgling learning management system in the late 1990s, they were met with a wall of disinterest.

When Matthew Pittinksy and the other founders of Blackboard attempted to find funding for the then-fledgling learning management system in the late 1990s, they were met with a wall of disinterest.

“‘We don’t invest in education,'” Pittinsky remembers investors saying. “‘We don’t do healthcare, and we don’t do education.'”

At the time, if a company wasn’t a large textbook company or a for-profit college, it was barely worth a glance to investors. Education was a large market, but one that was notoriously slow-moving and where the players were well-defined and largely resistant to sweeping technological changes.

“We were thinking, ‘how do you have as a rule that you don’t invest in education technology?’ Pittinksy says now. “But that was really the case. Across the country, it was very rare for a fund to make an education investment. There was no precedent for it.”

That began to change when, finally, a handful of investors took gambles on startups like Blackboard, a company that eventually sold for $1.6 billion in 2011. Suddenly there was precedent, but even those early investors couldn’t have predicted just how large the ed-tech startup market would become.

In 2002, according to the National Venture Capital Association, $146 million was being invested in ed-tech. By 2011, that number was $429 million. A year later: $1.1 billion.

2014, according to Tech Crunch, is well on its way to being another record year for ed-tech. More than $500 million has been raised in just the first year alone. Sometimes, it can feel a little like an episode of Oprah’s Favorite Things, with investors shouting “You get seed funding! And you get seed funding!”

So why, exactly, are we suddenly in such an ed-tech boom?

(Next page: How the recession created an opening for ed-tech)

The groundwork may have been laid in the early 2000s, but the explosion in interest really began in 2009. While most of the country was reeling from “the Great Recession,” investors poured an additional $150 million into ed-tech startups than they had in 2008.

The recession exposed deep flaws in higher education, Richard Demillo, director of the 21st Century Universities at Georgia Tech, said last year.

“Everything from cost to price to the mission of universities kind of went under the microscope,” Demillo said. “Enter technology.”

Learning management systems, digital (and open-sourced) textbooks, learning analytics, digital badges — if there’s a component of education that can be altered or replaced by technology, someone is trying to do that. And the money is there to help them make it happen.

Perhaps, the most visible example of this ed-tech craze are massive open online courses, or MOOCs. Coursera has now raised more than $80 million in funding, and just last month, its smaller competitor Udemy announced that it had raised $32 million in its most recent funding round.

At this rate, there seems to be little that can stop the flood of money rushing into ed-tech startups, but some are wondering if it’s a bubble about to burst. That initial worry venture capitalists had about the pace of change in education is still a real issue, and that can translate to slow — or nonexistent — returns for investors.

Ethan Beard, the former director of business development at Facebook and member of the eTranscript startup Parchment’s board of directors, said many investors are smarter and more patient than that, however. We’re only in the beginning stages of ed-tech investment, he said.

“Investors don’t like it, but they aren’t surprised if most of their investments fail, especially early on,” Beard says. “You expect most of them to fail and you hope to make it up on a few really big winners.”

(Next page: Ed-tech’s big IPO stumble)

But some critics worry that there are too few of those winners, and they point to the tiny revenue streams so far produced by many ed-tech companies — especially those making MOOCs — as cause for concern.

They also point to the initial public offering of the ed-tech company Chegg.

Expectations were high when the textbook rental service (and so-called “student hub”) announced it was going public in December. The price was set at $12.50 per share, but it dropped nearly 23 percent in one day. The reaction by journalists and insiders was harsh. Chegg didn’t just stumble; it fell flat, slumped, and was “the IPO disappointment of the week.”

Deborah Quazzo, founder of Global Silicon Valley Advisors, says the reaction to Chegg’s debut has been “much ado about nothing.”

“Obviously at Chegg, everyone would prefer it to go up, but the reality is that trading has very little to do with what a company does,” Quazzo says. “It becomes more of an art than a science.”

Chegg did manage to raise nearly $200-million in its debut. That’s more than the $150-million it said it was seeking in its original S-1 filing. IPOs are just the start of a longer process, she says, pointing to Facebook’s debut in 2012, which was widely seen as a disaster. The social network has since bounced back (albeit, slowly) and closed at its original IPO price.

“With IPOs, there are all kinds of psychological factors that come into play that don’t have anything to do with a company’s fundamentals,” Quazzo says. “I think you can read too much into factors outside of a company’s control.”

At the ASU-GSV summit in May, ed-tech executives Jonathan Harber, Jonathan Grayer and Chris Hoehn-Saric all agreed that there is an ed-tech bubble. At the same time, they said they weren’t sure if the bubble would burst any time soon, and the bubble can actually be a positive thing for now.

“It brings a lot of talent in,” Grayer said.

(Next page: Ed-tech’s “new normal”)

Pittinsky, one of Blackboard’s founders, also says ed-tech companies are likely in the midst of a bubble, but it’s not clear when the peak year will be, and the lack of MOOC revenue and impressive IPOs won’t do much to slow the tide any time soon.

Even if the bubble bursts, he said, ed-tech companies and venture capitalists have found a “new normal.”

“And the new normal is not the bubble,” Pittinsky says. “It’s the new comfort level by the investing community in education startups. The rate will always be much higher then it was in the mid-nineties. But we are just now getting to the time period for investors where these companies either need to prove they’re real or start flaming out.”

For educators — some who feel like they’ve been left out of the equation as ed-tech companies increasingly reach around universities to connect directly with students — there’s a more important question than if there’s an economic bubble.

Does any of this technology actually work?

Pearson, a giant learning company with far more resources than your average ed-tech startup, is just now beginning to assess its products’ effectiveness with its new efficacy reports. Pearson’s been selling learning products since at least 1942.

Four prominent research universities even recently announced the formation of a consortium, called Unizin, designed in part to address this lack of standards. “It’s tilting the table in favor of interoperability and university control,” James Hilton, the vice provost for digital education at the University of Michigan, says. “It’s about affirming that our faculty and students create unique learning environments, not the technology.”

Beard, of Parchment, says he strongly believes in the power of educational technology to address many of society’s ills, from poverty to health to unemployment. But that means students need to be able to easily find the application that’s right for them and that has a real, proven shot at helping them learn better.

“And I think we’re just now starting to connect those dots,” he said.

Jake New is a former editor with eCampus News.

- What does higher-ed look like in 2023? - January 5, 2015

- Are ed-tech startups a bubble that’s ready to burst? - January 1, 2015

- Are MOOCs really dead? - August 28, 2014