Key points:

- The digital humanities field is critically important to society

- The field was instrumental in one student’s journey to reveal more about ancient Egypt

- See related article: The synergy between art and technology in higher ed

- For more news on fields of study, visit eCN’s Teaching & Learning page

When Howard Carter first peered through a hole drilled into the wall of Tutankhamun’s tomb 100 years ago, he famously described what he saw as “wonderful things.” These days, after a century of Egyptologists and memoirists have pored over Carter’s documents, it is not clear if he actually said those words at that time, or perhaps said them later on, or perhaps not at all. He recorded the event in his own heavily rewritten notes, and the descriptor of King Tut’s tomb as a place of wonderful things has stuck throughout the decades.

The words we use to describe objects are contagious and long-lasting. Once something is known, it is finite and fixed in the historical record; it becomes a single story from a single mouth. But over time, more voices can appear. When new eyes have access to old documents and original materials, new interpretations begin to emerge. The first step in this process is always to bring those old materials into contact with new ways of thought.

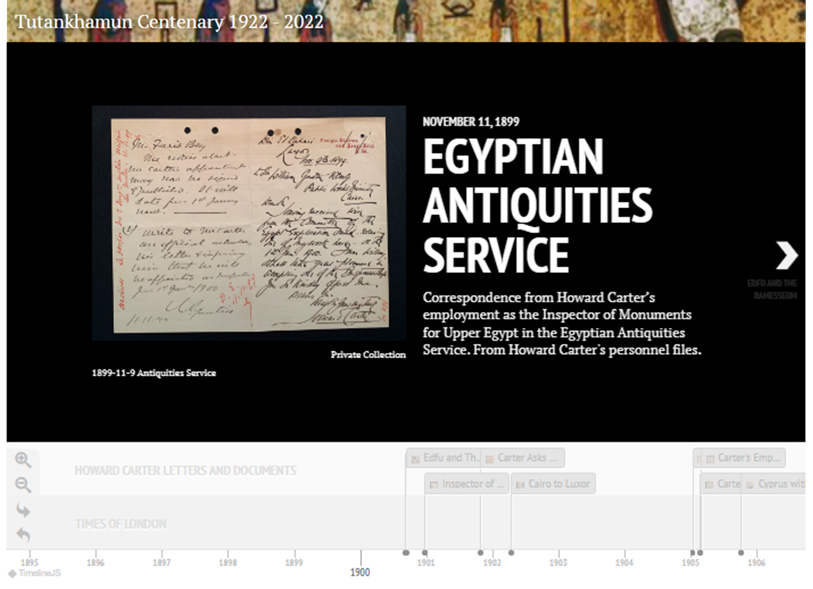

My reflections on the creation of the Tutankhamun Centenary 1922-2022 website, which functions both as an exhibit and a database of previously inaccessible materials describing the events of the excavation, come a few weeks after The Washington Post published an article titled “The most-regretted (and lowest-paying) college majors.” It probably won’t take you long to guess that the humanities and arts top the list. The article breaks down the ‘why’ behind the numbers and whether perception is reality. But then it stops to consider the more intersectional fields of study, and the digital humanities enter the discussion. As a humanities student with bachelor’s degrees in History and German Studies, a master’s in Medieval Studies, and now a Master’s of Library and Information Science (MLIS), I have seen the intersectional value of the digital humanities firsthand, and can say this: If you’re an institution, offer digital humanities courses; if you’re a professor, encourage your students to enroll in them; and if you’re a student on either side of the digital humanities divide, take a class.

Digitizing and collecting

The story of Howard Carter, Tutankhamun, and Tutankhamun’s tomb is as intricate and valuable as any treasure that was buried in the tomb. I came to their story not as an Egyptologist, but as a student of Library and Information Science at the University of Washington. There, I worked on a digital humanities Capstone project where I was part of a team that contributed to two firsts in the study of the excavation of Tut’s tomb. The Capstone team, which included three other MLIS students, worked in collaboration with Professor Sarah Ketchley, as well as the undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in her Digital Media: King Tut and Digital Humanities course, to analyze both articles from The Times of London about the excavation and some materials from a private collection of Howard Carter’s letters and documents.

Our first ‘first’ was building a collection of The Times Digital Archive articles that began in November 1922 when the paper announced the tomb’s initial discovery. The articles continued: In 1923, The Times announced its exclusive coverage of the tomb’s excavation; in 1924, it covered the legal debate over the closure of the tomb; and in 1925, it announced the tomb’s reopening and that the paper no longer held the exclusive rights to the story. Tutankhamun and the contents of his tomb marked a significant change in the landscape of newspaper reporting as The Times made a deal with Lord Carnarvon to be the sole disseminator of information and photographs of the discovery in exchange for its financial support of the excavation.

We weren’t the first to digitize The Times. We were granted access to the articles through Gale Primary Sources. In an interview we included on our website, Seth Cayley, Gale’s vice president of global academic products, explains that The Times archiving project began in 2002. We selected and indexed relevant articles from The Times, making them available as a set of public, searchable collections for the first time, so future interested parties won’t have to wade through all the issues of The Times to find the specific story they’re looking for.

The team’s second ‘first’ came about thanks to Professor Ketchley’s connection to a private collector who has spent the last 40 years gathering and preserving Carter’s letters and documents. Before that, the materials were scattered across the world after the last of Carter’s descendants passed away and were largely unseen by anyone other than his beloved niece and confidant, Phyllis Walker. The Tutankhamun Centenary website is the first chance for a selection of these items to be publicly available.

Exposure to digital humanities tools, vocabulary, and processes

Our team’s ‘firsts’ wouldn’t have been possible without a full docket of digital humanities tools at our disposal. In addition to the Capstone project exhibits on The Times and the Carter collection, the undergraduate and graduate students in the Digital Media: King Tut and Digital Humanities course also used The Times articles to create exhibits on Egyptomania. These exhibits examined how the discovery of King Tut’s tomb influenced advertising in British newspapers, and the Pharaoh’s Curse, which explores how newspapers reported on the so-called curse and the way it impacted sentiments surrounding the excavation of the tomb.

Our team used at least a half-dozen digital tools for gathering, preparing, analyzing, and displaying our materials and data. Each team used Gale Digital Scholar Lab (The Lab) as the foundation of their work. We relied on The Lab for its organizational tools, which were extremely helpful while we were collecting articles, allowing us to iterate our search terms for a wide spread of materials and then sort our newspaper finds into dedicated collections. We also used the optical character recognition (OCR) and correction tools within The Lab to transcribe more than 100 images of articles from The Times archive into plain text, which enhanced the searchability of our website. Lastly, I can personally say the metadata I was able to pull directly from The Lab as a downloaded spreadsheet likely saved me a month’s worth of work. We used other digital tools like Omeka, TimelineJS, and Tropy along the way to present and organize what we found.

The Lab was a great introduction to the variety of digital tools available for analysis and the vocabulary associated with each of them; while our Capstone team didn’t use the analysis tools within The Lab, the groups that worked on the Egyptomania and Pharaoh’s Curse portions of the website used them to create data visualizations like sentiment analysis and document clustering. The patterns they saw provided additional insights into the articles and advertisements they included in their collections, which they may not have been able to discern by going through each piece of material by hand.

There is still plenty of slow, careful work in digital humanities. Our team established guidance for The Times articles and the Carter collection that outlined our standards for article selection, OCR improvement, metadata input, and transcription. Standardization assures that each item is searchable and accounted for when using data visualization tools, so each group had to develop documents that would govern exactly what would go into each collection and how it would be labelled. Laying out that process clearly is a central tenet of digital humanities. Transparency about our approach to the materials and any potential shortcomings provides context for anyone relying on our research in the future. It’s also the kind of idea-sharing that could help other digital humanists in their work and vice versa.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

While the Capstone team was made up entirely of MLIS students, Professor Ketchley’s class included students studying psychology, global health, statistics, and informatics. The potential for intersectional collaboration in digital humanities benefits everyone; students interested in mathematics, computing, and science leave with a deeper understanding of history and historical research, while humanities students are exposed to tools they didn’t know existed, which opens new avenues for research and understanding. No field of study needs to be a monolith, and I truly believe that the humanities is a thriving field that can encompass both the traditional, deep-reading humanities and the broader, pattern-focused computer analytics humanities. There’s also little doubt that working with digital humanities tools impacts employment prospects in a world that largely requires technological proficiency. The creation of our website alone involved everything from learning to think critically about the sources we were using and how certain stories are told, to developing internal taxonomies and designing a website.

Our collaborative efforts also included volunteers. Twenty-two people from across the U.S., United Kingdom, Australia, and Italy stepped up to help us clean up The Times articles after they had been transcribed by the OCR tool within The Lab. We’ve been contacted by an Egyptian scholar who has begun translating The Times articles into Arabic so that they can be understood by the people whose ancestors made the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb possible. Our work will be incorporated into the archives at the Griffith Institute in Oxford and the American Research Center in Egypt. Lastly, it will be made available to visitors of the Howard Carter House in Luxor, where Carter lived during the excavation of King Tut’s tomb. We’re hopeful these collaborations will continue to build on what the Tutankhamun Centenary website started.

Expanding access to knowledge

This last point feels particularly important as a librarian and information scientist. Everyone wants access to knowledge; it’s just a matter of how easy it is to access. That idea has guided everything from what materials we included on the website to how we displayed them. Our goal was to create engaging exhibits, rich in information. We hope we’ve achieved that, but at the end of the day, we’re simply excited to have made dozens of primary source documents that lived in the archives available to anyone with access to the internet.

Primary sources provide insights that can’t always be gleaned from a textbook. By putting these 100-year-old words out there, we hope to give people the opportunity to draw their own conclusions. It is an undeniable fact that The Times coverage is also an account of how British imperialism dominated Ancient Egyptian excavations during the early twentieth century, but the articles depict a far more complex vision of British public opinion at the time of the excavation than we had anticipated. By providing access to primary documents written during that time, we hope to provide modern scholars with the chance to interact with that narrative directly, to look through it, and to explore what it might obscure. We hope these primary sources can be used to educate and inspire others in their work to restore the diversity of human experience within the historical record.

Working on this project reminded me many times of Borges’s short story, “The Library of Babel.” The eponymous library contains every possible arrangement of written characters, therefore capturing every story that could ever possibly be written. I thought of it often while correcting OCR text that generated gibberish, comparing it to scans of microfilms of articles published a century ago. I thought of it again while writing this reflection, particularly of a line from Andrew Hurley’s translation. Borges writes that each hexagonal gallery of the library contains only two light bulbs. “The light they give is insufficient, and unceasing,” he writes. Efforts to digitize and preserve old documents also often seem both insufficient, and unceasing. The work can continue, passing through format after format, media after media. However, when the work is perpetuated and made public, new discoveries can be made as more and more eyes alight on it and as the barriers to access are removed.