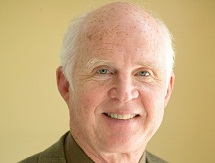

Taylor Branch spent 25 years crafting America in the King Years, a trilogy of popular books about the Civil Rights Movement. The work won him a Pulitzer Prize and cemented his reputation as one of the country’s most-respected historians.

He recently returned to the 2,300-page effort to condense it into a 190-page volume called The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement, now out in paperback.

The book also became an enhanced eBook featuring archival footage of historic interviews and speeches, and was the focus of an online seminar that Branch taught to 20 University of Baltimore students and 100 auditors tuning in virtually.

On the eve of the historic March on Washington‘s 50th anniversary, Branch talked to eCampus News about the challenges of teaching history with digital tools like massive open online courses (MOOCs) and eBooks, the difficulties of editing his own work, and the reasons why the Civil Rights Movement continues to captivate him.

eCN: In January, you taught an online seminar-style course based on The King Years. How was that experience?

Branch: Well, it was new. Let’s say that.

Part of the experience was testing the possibly that an online course could have any number of teaching assistants grading any number of online students, making sure that they were doing ideal work weekly. And that their grading would be in line with mine.

That may not be very exciting or sexy, but it does go to the question of “how do you maintain quality?” If you’re going to be asking universities to accept credit for this class based on more than just my reputation, you have to show a track record that students are doing work, and getting graded on it.

See Page 2 for details about The King Years as an eBook.

Is that your plan then? Do you hope to teach the seminar again, completely for credit?

Yes. We’re still nervous and formulating how we can offer it to a larger audience for credit. We’re working on that right now. A MOOC is not a business model. A MOOC is a gimmick for PR. We’re trying to figure out a way to make a seminar model that involves students effectively engaging in an expandable universe for credit online.

If it promises to significantly, dramatically, drastically cut the cost for students and open up access for credit that students who work for it can eventually use for a degree, that’s a service. And maybe a vitally needed one.

I really hope in the next month or two, we can get everything in so that we can get a course announced for next semester for credit through the University of Maryland.

Were there any challenges turning The King Years into an eBook?

I do not actually own a device in which I can read the enhanced digital version. My students didn’t use the online digital version, but I did help find all of the materials and videos. I’m not sure yet how much those enhancements really helped, if being able to actually listen to these Civil Rights speeches and interviews helped. It also raises all kinds of complicated issues of video rights, much more than quotation would in a book.

Most of the students, in the classroom and online, were talking about the printed book. I don’t know if that will be true the next time I teach it or not. Of course even with the paperback out now, the eBook is still cheaper. Even the enhanced eBook is cheaper.

All of this stuff is just so new that even the author doesn’t know parts of it.

How hard was it to condense such a large work into 190 pages?

It was difficult to pick the episodes, to boil things down, to do without 95 percent of the work that I slaved over for 25 years. But I thought it was worthwhile. I kept thinking of all the teachers over the years who have said that the storytelling approach to history was best, but that my books were too long for many students.

I thought it was necessary exercise. It made me really think about what was essential and what I was leaving out and how to give some sort of representative feel of that era. One of the toughest parts was the chapter about the middle Selma march. I had originally devoted 300 pages to Selma. Now I have just four or five pages focusing on that middle march.

You can always just summarize, but that sacrifices what the teachers and I believe is the advantage of teaching history with storytelling. There was blood on the floor. It wasn’t easy, but I’m glad I did it.

You’ve already devoted 25 years of your life and 2,300 pages to researching and writing about the Civil Rights Movement, but you’re still not done. What is it about this time in history that keeps compelling you to return to it?

I think that the lessons go very deep about what it means to be a citizen. Growing up a white southerner assuming our history was our treasure, it took me a long time to begin to see racial differences have always been at the heart of whether or not we’re going to live up to the promise of equal citizenship.

Black people in the fifties and sixties, they did what the founding fathers did. They pushed unjust hierarchy, subjugation politics in the direction of equal citizenship. It was hard for most Americans to recognize that they weren’t just doing something for themselves. They were doing something for all of us. In that sense, they were leaders for the whole country. I still don’t think that idea has sunk in for many people. I get a lot of push-back on that. Some people think the anniversary of the march is just a day for black people to celebrate a victory, to celebrate things that are no longer pertinent. It’s for everybody.

Race has always been at the center of what we mean by equal citizenship, and it still is.

Follow Jake New on Twitter at @eCN_Jake.

- What does higher-ed look like in 2023? - January 5, 2015

- Are ed-tech startups a bubble that’s ready to burst? - January 1, 2015

- Are MOOCs really dead? - August 28, 2014