Policy analyst says it’s a policy gap, not a skills gap, keeping students from careers

Is it really a skills gap that’s preventing college graduates from getting jobs, or is it a policy gap in how higher-ed institutions are governed and funded?

Is it really a skills gap that’s preventing college graduates from getting jobs, or is it a policy gap in how higher-ed institutions are governed and funded?

It’s the policy gap, says author of a new report, Mary Alice McCarthy, a senior policy analyst in the Education Policy Program at New America. According to McCarthy, colleges and universities are doing a good job of creating new career pathways and competency programs, as well as partnering with industry…they’re just not getting the right support.

“I explore the skills gap from a different perspective—as a gap between the policies governing higher education and the skill development needs of students, employers, and communities,” explains McCarthy.

In the report, McCarthy explains how the U.S. higher education system has become the largest provider of job training programs and what that means for students and institutions. She also delves into why current policies for delivering higher education do not work well for matching education and jobs.

Making her point, she identifies what she says are five policy gaps that are driving the poor results for students and employers.

“These policy gaps make it too easy for institutions to provide very low-quality career education programs while also making it too difficult for institutions to build the partnerships and programs that will facilitate student transitions to jobs and careers.”

(Next page: The 5 policy gaps in higher education; reframing the HEA)

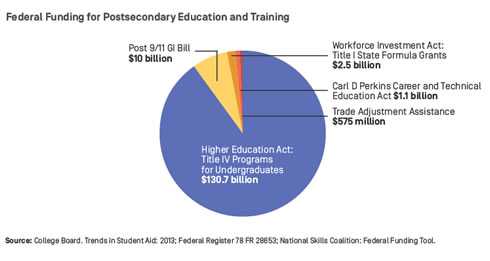

Established as part of the Johnson administration’s Great Society agenda, Title IV of the Higher Education Act (HEA) includes a suite of federal student aid programs that aim to extend the opportunity of a college education to all Americans regardless of means.

“Three of the core design elements of the financial aid programs have a large impact on how institutions recruit students, design programs and credentials, and deliver instruction,” says McCarthy; however, “these core design elements are the source of five ‘policy gaps’ between the needs of students in career education programs and the behavior of institutions of higher education.”

Policy gaps:

1. Accrediting institutions rather than programs: An accredited institution can have programs of widely varying quality, says McCarthy. “Students at an accredited institution are eligible for federal student loans for any credit-bearing program of study, but some may be much more likely to lead to good jobs than others. For a student entering a career education program, what matters most is how effective a particular program of study is at preparing graduates with the right mix of skills and credentials for work, not the overall quality of the institution.”

2. Looking inward rather than outward for indicators of quality: “The most obvious indicator of quality for a career education program is whether students transition successfully into jobs and careers,” emphasizes McCarthy. “ In strong contrast to the much smaller federal programs aimed specifically at career education or training, like WIOA, TAA, and Carl D. Perkins, employment outcomes are not considered a measure of quality in higher education accreditation processes. In fact, federal policies actually make it very difficult for institutions to track the labor market outcomes of students, even when they wish to.”

The report notes that other institutional behaviors that would be likely to improve transitions to employment, such as partnerships with employers, use of labor market information, and alignment with relevant industry standards, are also absent from accreditation processes.

“To the contrary, the accreditation system reinforces one of the primary impediments to delivering high-quality postsecondary career education—the tendency of institutions of higher education to look inward rather than outward for indicators of success,” McCarthy explains.

3. Ensuring the quality of degrees, but not certificates: “There is no agreement among accreditors as to the quality characteristics of an educational certificate, despite the fact that it is the fastest-growing postsecondary credential,” notes the author: “between 2001 and 2011 the number of certificates conferred by U.S. postsecondary institutions increased by 85 percent, from 572,000 to 1,057,000.39.”

4. Paying for time, not learning: Currently, time is a proxy for learning, the author explains, as students receive grants and loan disbursements based on their ability to complete a defined number of credit hours within an academic year.

“Whether they earn an ‘A’ or a ‘C-minus’ is irrelevant,” she says. “What matters from the perspective of the financial aid program is that they complete 60 percent of the credit hours for which they signed up.”

“A student aid program organized around learning, rather than time,” she continued, “would allow students to advance as they demonstrate competency in a particular subject area, regardless of when or where they obtained that proficiency.”

5. Rewarding enrollment, not outcomes: “It is a system that places the financial risk associated with higher education squarely on the backs of students,” says McCarthy. “There is nothing in the financing model that makes successful transitions out of college a jointly shared responsibility between student and institution.”

For more in-depth coverage of these five policy gaps, as well as recommendations for reframing the HEA, read the full report, “Beyond the Skills Gap: Making education work for students, employers, and communities” here.

- 25 education trends for 2018 - January 1, 2018

- IT #1: 6 essential technologies on the higher ed horizon - December 27, 2017

- #3: 3 big ways today’s college students are different from just a decade ago - December 27, 2017