In the race to build a faster computer chip, there is literally nowhere to go but up: Today’s chip surfaces are packed with the tiniest electronic switches the laws of physics allow, but Intel Corp. says it is blowing past those limits with a breakthrough, three-dimensional transistor design it revealed May 4.

Analysts call it one of the most significant developments in silicon transistor design since the integrated circuit was invented in the 1950s. It opens the way for faster smart phones, lighter laptops, and a new generation of supercomputers—and possibly for powerful new products engineers have yet to dream up.

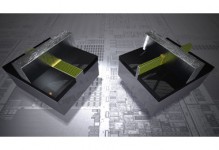

Minuscule fins jutting from the surface of the typically flat transistors improve performance without adding size, just as skyscrapers make the most of a small square of land.

“When I looked at it, I did a big, ‘Wow,’” said Dan Hutcheson, a longtime semiconductor industry watcher and CEO of VLSI Research Inc. “What we’ve seen for decades now have been evolutionary changes to the technology. This is definitely a revolutionary change.”

Intel CEO Paul Otellini said that “amazing, world-shaping devices” will be created using the new technology.

Computers are already doing things that were almost unimaginable when Intel co-founder Gordon Moore made his famous prediction in 1965 that computers should double in power every two years.

The axiom, known as Moore’s Law, has held true ever since as computers have gotten cheaper, smaller, and more powerful.

Engineers believe Intel’s new transistors will keep the axiom going for years to come. Chips with the 3-D transistors will be in full production this year and appear in computers in 2012.

When Moore’s Law was first coined, the most advanced computers were large, mainframe-type machines that took up entire rooms and were best suited for narrow tasks done one at a time.

Today we have smart phones that let us carry around the internet in our pocket, supercomputers that have beaten Jeopardy! and chess champions, and even experimental cars that drive themselves.

Technologists entertain visions of even deeper integration of artificial intelligence into our lives as computer technology advances, such as robots performing surgery.

Transistors, tiny on/off switches that regulate electric current, are the workhorses of modern electronics. They’re to computers what synapses are to the human nervous system. They have become faster over the years thanks to new materials and manufacturing techniques, but Intel’s latest advance is a redesign of the transistor itself.

A chip can have a billion transistors, all laid out side by side in a single layer, as if they were the streets of a city. But chips have had no “depth”—until now. On Intel’s chips, the fins will jut up from that streetscape, sort of like bridges or overpasses.

The fins give the transistor three “gates” to control the flow of electric current, instead of just one. That helps prevent current from escaping. There’s a limit to how much current a chip can take, and the new design allows more of that power to be spent on computing rather than being wasted.

Intel has been talking about 3-D, or “tri-gate,” transistors for nearly a decade, and other companies are experimenting with similar technology. Intel’s May 4 announcement is noteworthy because the company has figured out how to manufacture the transistors cheaply in mass quantities.

Other semiconductor companies argue that there’s still life to be squeezed from the current design of transistors, but Intel’s approach allows it to advance at least a generation ahead of rivals such as IBM Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc.

Intel’s approach carries some risks, because the technology is untested on the mass market. But Doug Freedman, an analyst with Gleacher & Co., said Intel’s approach might actually reduce chip defects if the multiple gates make the transistors more reliable.

“Intel takes big gambles when it knows what it’s doing,” Freedman said.

The reduced power consumption also addresses a key need for Intel, which is the dominant maker of chips for personal computers but has been weak in the growing markets for chips used in smart phones and tablet computers. Intel’s current chips use too much power for it to be competitive in those markets, and the 3-D chips could help it become more of a player.

Transistors are microscopic, but their performance is felt with every click of a mouse, tap on a smart phone, or download from a website. The faster they twitch, the faster a computer “thinks”—and sucks up power.

They need to get smaller without leaking too much power, a worrisome issue as the materials reach the atomic scale and get worse at blocking current from escaping.

Intel’s advance does not add a complete third dimension to chip-making—that is, the company can’t add an entire second layer of transistors to a chip, or start stacking layers into a cube.

That remains a distant but hotly pursued goal of the industry, as cubic chips could be much faster that flat ones while consuming less power.

And the technological advance Intel has achieved won’t guarantee success, as Intel has learned in repeated attempts at cracking the mobile market. The performance expectations and power requirements for phones and tablet computers are not as high as those for PCs.

Other chip makers, such as Qualcomm Inc. and Texas Instruments Inc., have entrenched partnerships with cell-phone makers that Hutcheson, the industry watcher with VLSI Research, said will be tough to overcome.

“When it comes to the mobile market, they have their work cut out for them,” he said. But “this gives you the transistors to build the next great system.”

- Research: Social media has negative impact on academic performance - April 2, 2020

- Number 1: Social media has negative impact on academic performance - December 31, 2014

- 6 reasons campus networks must change - September 30, 2014